Innerlijke vrijheid vinden: Persoonlijke transformatie

Nu de winter zijn intrede doet, is het tijd om naar binnen te keren en na te denken over onszelf als deel van het geheel.

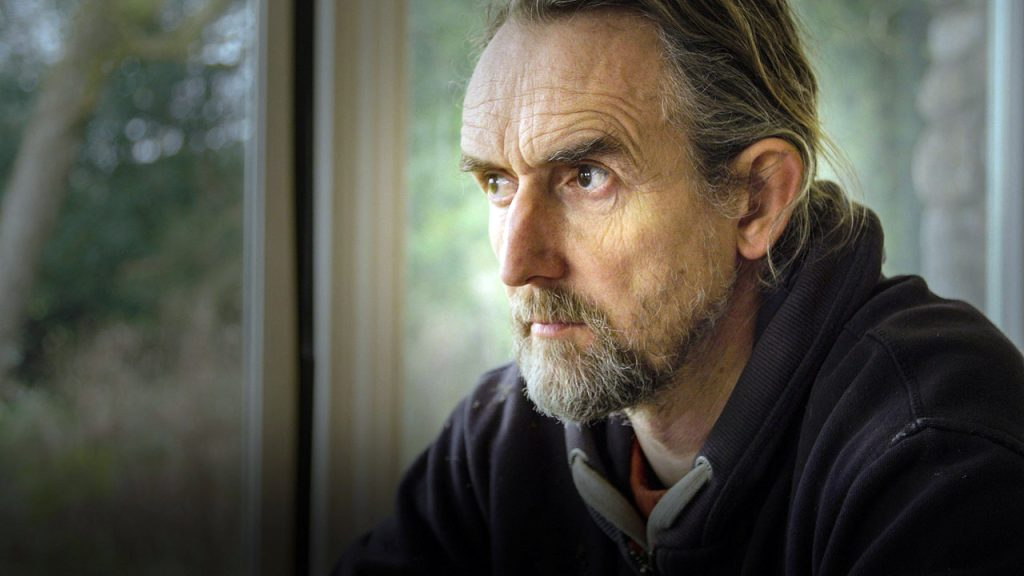

In deze aflevering van The Spirit of Revolution verken ik de aard van het zelf en hoe het begrijpen ervan cruciaal is voor zowel persoonlijke als collectieve actie. Ik deel mijn eigen worstelingen met depressie en burn-out, en hoe ik de kracht van transcendentie ontdekte - het loskoppelen van het "ik" van de emoties en overtuigingen die ons gevangen houden.

Dit gaat niet alleen over mentaal welzijn; het gaat over het vinden van de innerlijke kracht om de crises waarmee we geconfronteerd worden te weerstaan. Door op onszelf te leren reflecteren, ontsluiten we het vermogen om te handelen zonder verteerd te worden door wanhoop. Deze reis gaat over het samen opbouwen van veerkracht terwijl we ons voorbereiden op wat komen gaat.

Sluit je bij me aan als we de weg beginnen van zelfbewustzijn naar revolutionaire actie.

Luister op Spotify, Apple, Soundcloud of waar je je podcasts ook vandaan haalt. We hebben gewerkt aan het verbeteren van de geluidskwaliteit van de gevangenis telefoon en elke aflevering zal worden geleverd met een nieuwsbrief transcript en video versie op Youtube om mee te lezen.

Aflevering 3 - Het Zelf

Je zou kunnen zeggen dat ik in de overtuigingsbusiness zit. Voordat ik betrokken raakte bij deze surrealistische taak om te proberen de sociale ineenstorting en het uitsterven van mensen te stoppen, runde ik kleine bedrijven en veel van dat werk gaat over het overtuigen van mensen om dingen te kopen, om voor je te werken, enzovoort. Er zijn een aantal vuistregels. Eén daarvan is dat je mensen niet in één keer van nul naar honderd kunt brengen; ze verdwijnen gewoon. De meeste van onze hersenen moeten meestal fases doorlopen.

Ik heb zo'n 200 lezingen en interviews gehouden over dit doodsproject waar we mee te maken hebben - wat de oppositie klimaatverandering noemt. Je kunt mensen niet meteen vertellen dat ze doodgaan; je moet het stap voor stap doen en voorbeelden geven van elke fase van de uitleg. Ik begin met het idee dat dingen echt zijn - echt in de zin dat ze je pijn kunnen doen en kunnen doden. Voor de hand liggende dingen, zoals van een gebouw afspringen - dat doe je en je gaat dood, ja, en daar zijn ze het allemaal mee eens. Vervolgens vraag ik hen: Wie vertrouwen ze om hen de waarheid te vertellen over zaken van leven en dood? Bijvoorbeeld, als je een knobbeltje in je lichaam hebt, ga je dan naar je vriend om een diagnose te krijgen? Nee, je gaat naar de dokter, en daarna misschien naar een professionele specialist die al tientallen jaren kijkt naar gevallen zoals het jouwe. Het is je recht, en het is je verantwoordelijkheid, om de waarheid te horen.

Dus, van wie wil je het horen als het gaat om het in de lucht brengen van broeikasgassen? Dat zijn natuurlijk de wetenschappers die jarenlang naar de situatie hebben gekeken. Zij kunnen je de ruwe feiten geven en vervolgens hun interpretaties en enkele voorspellingen over die feiten. Pas nadat ik dit allemaal in een praatje heb gedaan, ga ik verder met waar het echt om gaat: Wat betekent dit allemaal met betrekking tot koolstofuitstoot? Pas als we zien wat het werkelijk betekent, accepteren we dat het echt is.

Ze helpen mensen door de afschuwelijke informatie die ze krijgen. Ze moeten zich bewust zijn van hun emotionele reacties. Hebben ze de pijnlijke overstap gemaakt van de ene reeks overtuigingen naar de andere? Dit is de bevrijdende overgang van cognitieve dissonantie - ruzie met jezelf - naar de resolutie om actie te ondernemen met anderen, de congruentie tussen overtuiging en actie, die cruciaal is voor welzijn, de gezondheid van de ziel, zoals je het zou kunnen noemen.

Dit is dus het proces dat ik de komende paar afleveringen ga volgen. We gaan kijken naar het zelf, de wereld en dan de tijd. In deze aflevering kijken we naar het zelf. Ik vraag je om even geduld te hebben; het lijkt in eerste instantie misschien niet zo voor de hand liggend, maar de reisrichting is in feite hoe je de wereld redt, zoals jij het graag noemt.

Ik neem je mee op een omweg, waarvan de eerste etappes misschien niet bijzonder relevant lijken. "Wat heeft dit ermee te maken?" zou je kunnen zeggen. Maar misschien wil je je de inleidende aflevering herinneren over het vonnis, de beschrijving van mijn reacties en gevoelens, hoe ik zag wat er aan de hand was.

We zouden kunnen nadenken over de vraag waarom heilige mensen enorm invloedrijk zijn, zelfs machtig, zou je kunnen zeggen. Dat is niet omdat ze toegang hebben tot dwingende macht, veel geld of wapengeweld, maar eerder omdat ze een bepaalde manier hebben om de wereld te zien. Ze zien de wereld niet als een verzameling echte dingen, in het bijzonder - je zou ze idealisten kunnen noemen als algemene regel. Ze zien de wereld als afhankelijk van de geest.

Natuurlijk denken we niet dat we allemaal plotseling heiligen kunnen worden in een of andere klassieke zin, maar ze laten wel een nieuwe reisrichting zien. Net als de pioniers van de sociale beweging zijn ze in die zin instinctief idealistisch. Ze zijn niet verslaafd aan de wereld; hun geest is erop gericht, gedreven zelfs, om de wereld te veranderen. Ze zien dit niet als een doel op zich.

Maar de tweede stap is dat de mensen die meedoen als het eenmaal is opgezet en helpen om het van de grond te krijgen, moeten worden geïntroduceerd in deze manieren van denken. Ze moeten worden meegenomen op een reis van etappes langs een pad. Deze podcast kijkt dan naar manieren om gewone mensen, zoals je zou kunnen zeggen, mee te nemen op deze reis naar veerkrachtige, revolutionaire collectieve actie. Mensen komen daar niet vanzelf.

De algemene benadering is dan om empirie te gebruiken - en daarmee bedoel ik observatie - om ons in staat te stellen vraagtekens te zetten bij wat ons verteld is over de werkelijkheid, het echte. We hebben de neiging om te geloven dat de waarneming van de werkelijkheid hetzelfde is als de werkelijkheid waarvan ons verteld is dat die bestaat, maar zoals we zullen zien, gaan ze al snel uit elkaar, of in ieder geval worden de dingen al snel ingewikkeld. Wat wij als echt beschouwen is zeker te simplistisch. Het heeft bijvoorbeeld de neiging om niet met de tijd mee te gaan en de conventionele kijk op de werkelijkheid wordt door de machtigen gebruikt om mensen te domineren, om hun zin te krijgen.

Paradoxaal genoeg zijn er dus echte problemen met de werkelijkheid.

Een klassiek voorbeeld hiervan is economie, dat oorspronkelijk een onderwerp was met verschillende perspectieven, maar dat na verloop van tijd gereduceerd werd tot een focus op wiskundige modellen die afhankelijk waren van een specifieke aanname over motivatie - dat motivatie een functie is van materieel individueel eigenbelang. In de afgelopen decennia heeft een hernieuwde interesse in empirische observatie aangetoond dat mensen soms, vaak in feite, niet handelen zoals economen aannemen. Ze handelen niet volgens dit veronderstelde eigenbelang. Het concept zelf van eigenbelang wordt zeer problematisch - wie kan zeggen wat het eigenlijk is?

Het probleem is niet dat de benadering nutteloos is, maar eerder dat ze, net als alle praktijkvoorbeelden van de werkelijkheid, beperkt is. Er zijn veel meer spelletjes in het spel. Dit is dus het plan: de eerste stap is dat we het idee van meervoudigheid aanvaarden. Hoe jij de wereld op dit moment ziet, is niet het laatste woord. "Mezelf" zou niet alleen X kunnen zijn; het zou ook Y en Z kunnen zijn, allemaal tegelijkertijd. Wat we aan het doen zijn is als beginnen met een training in een mentale sportschool - je wordt flexibeler. En dit proces zal natuurlijk steeds urgenter worden naarmate de sociale omstandigheden om ons heen verslechteren.

De manier van kijken die een aantal eeuwen geleden is vastgelegd door een stel slimme blanke kerels, een aantal dogma's, zal de komende jaren niet meer zo goed van pas komen. De stelling van deze podcast is dat we nieuwe perspectieven nodig hebben en dat deze nieuwe perspectieven aan de basis moeten liggen van hoe we sociale actie ondernemen, van hoe we onze organisaties leiden.

Dus laten we beginnen. Ik ga wat dingen doorploegen en misschien zal ik wat thema's weer oprakelen. Het zal niet eenvoudig zijn, maar het is nodig. Laten we eens naar het zelf kijken. Ik schrijf op een blad papier op een tafel in mijn cel. De tafel is hier. Ik kan het zien - het bestaat. Als ik aan mezelf denk, of kritisch, als ik daar twee woorden van maak - "mijn" en dan "zelf" - stuit ik op een fundamenteel probleem. Ik kan dit zelf waar ik naar kijk niet zien, wat betekent dat ik het niet op dezelfde manier kan zien als ik deze tafel nu voor me kan zien.

Dit solide ding in mijn gezichtsveld - het zelf - zou je verborgen kunnen noemen. Het is er niet echt fysiek. Je zou kunnen zeggen dat het onzichtbaar is, maar het is er nog steeds in zekere zin, niet in het minst omdat als het er niet was, ik de tafel niet zou kunnen zien. Hele boeken, tientallen jaren van levens, zoals je misschien weet, zijn gewijd aan pogingen om dit allemaal uit te zoeken, pogingen om de tegenstrijdigheden - of wat we de paradoxen zouden moeten noemen - die betrokken zijn bij wat ik zojuist heb gezegd, recht te zetten. En het is eerlijk om te zeggen, denk ik, dat een aantal van de knapste koppen in de geschiedenis hierover in kringetjes hebben rondgedraaid.

De aanpak die ik in deze podcast wil voorstellen, is om te bedenken dat dit misschien eigenlijk geen probleem is. Je kunt je hoofd erover krabben, het dan vergeten, gaan wandelen en de hemel valt niet in. Je zult morgen waarschijnlijk nog leven als je besluit dat je de grootste tegenstellingen van het leven niet kunt oplossen - niet in de laatste plaats de relatie tussen het zelf en de wereld.

Wat ik voorstel is natuurlijk geen nieuwe aanpak. Sommige mensen noemen dit antwoord "pragmatisme". Let op het woord "antwoord" in plaats van "antwoord". Let ook op wat een doorlopend thema zal worden - dat empirisch onderzoek, indien eerlijk ondernomen, een hulpmiddel is om te ontdekken dat het werkelijke het werkelijke ondermijnt. We worden zeker van de gegrondheid van dit ding, het zelf, en ook van dit ding, de wereld.

Mijn doel is dus simpelweg dit: een gevoel van vloeibaarheid creëren, een metafysische pluraliteit, als je dat lange woord wilt gebruiken. Laten we terugkeren naar ons verhaal hier. Waar zijn we naartoe? We zeggen dat er een fundamenteel verschil lijkt te zijn tussen de aard van de tafel - dit ding in de wereld - en dit ding dat de ik-persoon wordt genoemd. En er is een probleem: wat komt eerst, het bewustzijn of de wereld? Idealisme of realisme, zoals de technische termen in de westerse filosofie zijn.

Maar dan zijn er meer moeilijkheden, zoals de oneindige regressie van dit zelf. Ik bekijk mezelf, prima, maar wat of wie is het "ik" dat naar mezelf kijkt? Wat is dat ding dat ziet, dat kijkt naar het "ik" dat naar mezelf kijkt? In principe is er geen reden waarom je deze vraag niet ad infinitum kunt blijven stellen - voor altijd, zonder einde. Lastig.

Misschien kunnen we in dit stadium zeggen dat er twee categorieën zijn - dit zou onze voorlopige halteplaats kunnen zijn. Er is dit ding, de wereld, en er is dit ding, het zelf. Het laatste is er, je kunt het alleen niet zien. De aard van het zelf is dan wat ik opgeschort zou willen noemen. Het lijkt geen solide basis te hebben, of in ieder geval kunnen we er geen vinden. Maar dit betekent absoluut niet, in zekere zin, dat het niet echt is. Let op dat woord "zin" - die realisatie is een belangrijke stap op onze reis naar de erkenning van de opgeschortheid van een ding. Het is oké. Het is emotioneel aanvaardbaar voor ons. We rennen niet bang de kamer uit. Zoals ik al zei, de hemel valt niet naar beneden.

Het belangrijkste punt is dat we niet hoeven te kiezen tussen deze binaire situatie - tussen echt en niet echt. Als het eenmaal goed voelt, zijn we op weg. Misschien is het een beetje zoals de posters op de muren van de gevangenis waar ik zit. Ze zeggen: "Sommige mensen zijn homo. Zet je er overheen." Je accepteert de dingen zoals ze zijn en opeens komt het gloeilampmoment: het is goed, het leven gaat door. We zullen later bespreken hoe dit proces meer te maken heeft met emotie, met onze psychologie, dan met een 18e-eeuws idee van verfijnde rede.

Dus nu hebben we dit idee van ophanging. Wat nu? Wat dacht je van functionaliteit, wat betekent dat je iets kunt doen met deze situatie. Dat wil zeggen, iets kan nuttig voor ons zijn. Het is therapeutisch en het kan ons helpen deze wereld te redden. Laten we even nadenken over depressie. Nogmaals, er is heel veel geschreven over depressie, maar ik wil er iets heel simplistisch over zeggen: depressie gaat over vastzitten.

Wat betekent het om vast te zitten? Als mensen zeggen: "Ik ben depressief," erkennen ze fundamenteel niet de aard van het woord "ik" in die zin - de "ik" die kijkt naar mij die depressief is, wat de realisatie betekent dat er twee dingen zijn: de "ik" en dan de "ik" die depressief is. De "ik" is dan niet depressief. De "ik" kijkt naar de depressieve "ik". Als dit eenmaal gerealiseerd is, is er in principe een ontsnappingsroute - het "ik" kan de ontsnapping organiseren. De realisatie is dat je in feite je depressie niet bent. Je bent het niet.

Dit besef kan ontstaan door na te denken over twee verwante ideeën. Ten eerste is er de zelfreflexiviteit - het vermogen om jezelf te zien en te beseffen dat dat is wat je doet: jezelf zien, het "ik" dat naar zichzelf kijkt. Sommige mensen zitten zo in zichzelf dat ze, zoals je zou kunnen zeggen, het bijna onmogelijk vinden om uit zichzelf te komen. Ze zitten vast, verstrikt.

Kinderen zijn vaak zo. Ze worden letterlijk overweldigd door hun emoties. Het is alsof ze hun emoties zijn. Ze worden meegesleurd door een enorme stroom van zijn - ze kunnen zichzelf er niet uit halen. Het probleem strekt zich natuurlijk uit tot in de volwassenheid. We ervaren het allemaal. Je ziet het veel in de gevangenis - mensen die zo vol zijn van hun verdriet, hun woede en razernij, dat ze zichzelf helemaal niet kunnen zien. Tegelijkertijd zit de gevangenis ook vol met mensen die, paradoxaal genoeg, heel goed zijn geworden in het bewust zijn van zichzelf. Ze hebben het op de harde manier geleerd, zou je kunnen zeggen. Ze komen tot het besef dat een gebrek aan zelfreflexiviteit een groot probleem is, waardoor ze niet verder kunnen en hun leven niet kunnen leiden.

Er is hier dus meer aan de hand dan een filosofisch raadsel, nietwaar? Het vermogen om over jezelf na te denken, over je emoties en je gedrag, leidt tot een algemener idee - misschien wel het centrale idee van deze podcast - en dat is transcendentie. Dit zou je kunnen omschrijven als een diep vermogen om buiten jezelf te treden, om van buitenaf naar jezelf te kijken, gewoon om te *kijken.* Zoiets. Woorden vatten het niet helemaal, maar ik hoop dat dit voor nu een definitie is die goed genoeg is om mee verder te gaan. Dit vermogen is wat ik de meta-therapeutische beweging zou willen noemen. Het is een diep structureel iets - het vermogen om te zien dat je niet je depressie bent, bijvoorbeeld. In feite ben je eigenlijk *iets* ten opzichte van iets. Dingen als depressie zijn eigenlijk constructies. Als zodanig zijn ze niet solide. Je zit niet vast. Je kunt eruit komen en ontsnappen, of in ieder geval is de situatie niet hopeloos, ook al voelt het wel zo.

En er zijn natuurlijk veel therapeutische benaderingen en praktijken die vanuit dit idee werken - dat mensen deze ontsnappingsroute kunnen zien. Het is dan een beweging, een overgang van starheid naar vloeibaarheid. En natuurlijk werkt dit proces niet altijd. Was de wereld maar zo eenvoudig! Zoals we al hebben gezegd over deze reis, doen de gloeilampmomenten zich voor en dan, vervelend genoeg, vallen ze terug - wij vallen terug. We zijn allemaal verschillend; we hebben verschillende persoonlijkheden.

Een andere scène die we gaan bekijken: het is een grote fout om te denken dat iedereen hetzelfde is. Dat zijn we niet. Dit brengt ons bij het eindpunt van deze podcast. Laten we daar eens naar kijken: de reisrichting. Ik zal het illustreren met twee persoonlijke verhalen om deze aflevering af te sluiten.

Toen ik een tiener was, was ik niet gelukkig. Afgezien van alle standaard, ondraaglijke uitdagingen van het navigeren van een route van kindertijd naar volwassenheid, vond ik mezelf eindeloos woedend en bitter over de onrechtvaardigheden van deze wereld. Niet in de laatste plaats het lumineuze idee dat sommige mensen hadden dat het goed zou zijn om, onder bepaalde omstandigheden, kernkoppen zo ver te laten gaan dat er een nucleaire winter zou komen, wat de dood van de hele mensheid in een paar weken zou betekenen.

Ik had er een paar slapeloze nachten van. Tegen de tijd dat ik 21 was, had deze woede zich uitgebreid naar het hele systeem - het hele systeem dat deze mogelijkheid mogelijk maakte - en breidde zich kritisch uit naar de andere activisten met wie ik werkte. Ze wisten wat er aan de hand was en toch waren ze duidelijk niet in staat om hun gewicht in de schaal te leggen, aangezien de mensheid op de rand van totale vernietiging stond. Dit is een bekende spanning in de radicale cultuur, en ik was een extreem geval.

Toen had ik letterlijk een openbaring op een dag - het kwam uit het niets, een gloeilamp moment. De openbaring was de volgende: ik kan proberen de wereld te redden en me daarbij totaal ellendig en bitter voelen, of ik kan proberen de wereld te redden en besluiten *niet* totaal bitter en ellendig te zijn. De keuze leek ineens kristalhelder. Ik kon mijn acties scheiden van mijn gevoelens-ah-ha! En het zou me een veel effectievere activist maken door niet de hele tijd zo'n irritante klootzak te zijn. Je kent het type wel.

In de praktijk betekende het dat als ik 's ochtends wakker werd - tenminste op een goede dag - ik geen verwachtingen had van andere mensen. Ik deed mijn best, deed wat ik kon, en raakte niet gehecht aan de acties, of het gebrek daaraan, van anderen. Dit weerhield me er niet van om me depressief en boos te voelen, maar er was een fundamentele verandering opgetreden: nu wist ik dat er objectief gezien een ontsnappingsroute bestond. Ik hoefde mezelf niet te vermaken, zoals ik dat pleeg te zeggen. Ik had een keuze.

De daad van transcendentie is als een fysieke spier - hoe meer je oefent om het te doen, hoe sterker je erin wordt. Hoe meer ik bewust besloot om mezelf en mijn situatie, mijn emoties en de ellende van deze wereld te overstijgen, hoe beter ik erin werd. En zoals velen van jullie weten, weet ik zeker dat dit een levenslange reis en uitdaging is.

Dus toen ik in de 30 was, had ik een heel slechte ervaring. Een half jaar of zo daarna, elke ochtend als ik wakker werd, ging het even goed met me, en dan herinnerde ik het me-*bang*-het raakte me als een moker: een overweldigende depressie.

Ik werd overspoeld door een gevoel van zelfverachting. Ik kon niet begrijpen waarom ik nog leefde. Ik wilde dood en maandenlang was ik hulpeloos om het te stoppen - zo intens was het. Ik wist alleen dat ik zou moeten wachten. Heel geleidelijk herkende ik mezelf. Ik herontdekte het "ik" dat kon toekijken hoe ik werd onderworpen aan dit monster. Ik stelde het me een beetje voor alsof ik in een kamer was met een razend, stinkend ding dat me tegen de muur duwde, zodat ik me niet kon bewegen. En dan weer bedacht ik gaandeweg een manier om erlangs te komen zonder dat het het merkte en door de deur te ontsnappen. En dan ging het een tijdje goed. En dan kwam het weer terug en zat ik weer vast tegen de muur.

Misschien had ik geluk, was ik gezegend met dit vermogen om weg te glippen, of misschien was het een aspect van mijn persoonlijkheid - wie zal het zeggen? Maar er was zeker een element van persoonlijke agency. Voor een deel was het omdat ik wist van dit transcendentie-ding, deze verdorde spier die sterker kon worden door het te gebruiken. Zoals ik al zei, ik ontdekte het in mijn twintiger jaren en heb het sindsdien ontwikkeld. Deze ervaring was dus een soort spoedcursus voor gevorderden om dingen naar een hoger niveau te tillen. De hele ervaring heeft me enorm gesterkt. Ik ben veel veerkrachtiger geworden. Wat er ook met me gebeurt in deze wereld, wat er ook gebeurt, zal gebeuren met *mijzelf*, het zelf, niet met de "ik" die naar het zelf kijkt. Het "ik" is, op een fundamentele manier, niet van deze wereld - zoals ze zeggen - het kan niet geraakt worden door de wereld, hoe verschrikkelijk die ook is.

Om dit te beseffen, is het aanvoelen van de bron van een heel ander soort kracht - een kracht die niet gebaseerd is op deze wereld, maar die ergens anders vandaan komt. Dat brengt ons terug bij het grote idee van deze podcast, de kernstelling waarop we zullen voortbouwen: dat we effectief kunnen reageren op de alomtegenwoordige burn-out die het verzet ondermijnt dat we op dit moment nodig hebben, die ons vermogen verlamt om dienstbaar en solidair op te treden, om ons te verenigen om te reageren op de echte crisis die er is. We kunnen ons realiseren dat al onze afschuw over wat er in deze wereld gebeurt, in feite kan worden overstegen.

De essentie van mens-zijn heeft niets te maken met ons zijn *in* deze wereld - het heeft te maken met het hebben van een keuze. De keuze om te transcenderen of niet te transcenderen, de keuze om te realiseren of niet te realiseren. We zijn kinderen van God, zoals men vroeger zei. Maar om terug te keren naar de praktische kant van de zaak, dit alles gaat over precies dat - beoefening, in beide betekenissen van het woord. Ten eerste, om te oefenen als een alleenstaande, om zelfreflectie zodat het een tweede natuur wordt. Zodat je kunt zeggen: "Ooh, er komt iets groots aan - ik moet op mezelf letten", zoals bij mijn verdict-ervaring, in plaats van te zeggen: "Er komt iets groots aan - ah!". En ten tweede, in eclectische zin, om een praktijk met anderen in gemeenschap aan te gaan. Als we hier allemaal mee beginnen, gaat het om collectieve rituelen, gebeurtenissen die mensen samenbrengen, zodat we ons realiseren dat we niet alleen zijn. We zijn al samen; we moeten ons dit alleen realiseren en die saamhorigheid in praktijk brengen.

Dit is dus de reisrichting. Nogmaals, zoals ik al zei, denk niet dat je dit nu allemaal op een rijtje moet hebben op basis van wat ik net heb gezegd. Je hoeft geen definitief oordeel te vellen - doe dat alsjeblieft niet. Je kunt er gewoon mee zitten en zeggen: "Ja, ik snap het wel, het klinkt interessant." In de volgende aflevering ga ik verder met de andere twee dingen: de wereld en tijd.

Zoals altijd kun je je aanmelden voor geweldloos burgerverzet bij Just Stop Oil in het Verenigd Koninkrijk of via het A22 Netwerk internationaal. Als je betrokken wilt raken bij de democratische revolutie, doe dan mee aan een komende Welcome to Assemble lezing.